The Book of Baruch in the Old Testament has this to say:

People, look east.

The time is near

Of the crowning of the year.

Make your house fair as you are able,

Trim the hearth and set the table.

People, look east, and sing today:

Love the Guest is on the way.

As you know in the past few months at Mass we have begun to face East again. This was suggested recently as preferred practice by Cardinal Sarah and rather divides opinion in some areas of the Church. There would be good reason for suggesting that when we worship in Advent we should all face east. This is not because of some nostalgia for the good old days before liturgical renewal when priest and people all faced the east. But rather because of that cry,

People, look east, which encapsulates so much of the spirituality of Advent.

Why this emphasis on the east? Well, its origins are in the way certain Old Testament texts were applied to Christ by the early Christians. The sun is the dominant light in our human experience. But Christ is seen as a greater Sun. So, in the Book of Malachi, Christ is the fulfillment of the prophecy of the ‘Sun of Righteousness, who will rise with healing in his wings’. In Psalm 19, Christ is the Sun, ‘who comes forth as a bridegroom out of his chamber and rejoices as a giant to run his course, who goes forth from the uttermost part of the heaven and runs to the very end again’. And because he is the true Sun, he is also the true dawn. So in the Benedictus, Christ is the promised ‘dayspring from on high’, who gives light ‘to them that sit in darkness and in the shadow of death’. In beholding the rising sun, the cosmos itself witnesses to Christ, the ‘true and only Light’.

O oriens, we cry in this season as one of the great Advent antiphons.

O Dayspring, Brightness of Light everlasting, and Sun of righteousness. Come and enlighten those who sit in darkness and in the shadow of death.

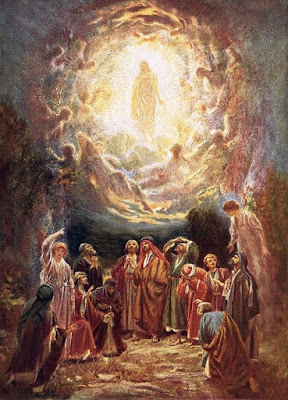

So Advent orients us, or re-orients us towards the east. Advent brings together the Christ who came in the great humility of his first coming; who comes to us daily through his words and his sacraments, who will come, as surly as the sun will rise, as the dawn will break. People, look east.

In Advent, the nights are long; we yearn for the coming of the day, the coming of the light. In December, on certain days, the dawns are magnificent - in the past few days few of us can have missed the beautiful clear, sunny daybreaks. A beautiful dawn becomes its own sermon.

People, look east – and see the promise of God’s glory; a glory we now glimpse in the shining splendour of light.

But as the evenings continue to draw in the sun sets all too early. The growing darkness of this season encourages us to look east: not in wonder and amazement but in expectation. We wait, however long, for the next daybreak. The Church too in this season remains undaunted by the wait for Christ's return in glory, for we know that when it comes it will be worth the wait. Stay awake! Watch! Pray! Advent is a season to grasp again the reality of salvation to enable us to live by faith and not by sight, to ‘see the invisible’. Wordsworth’s

Ode speaks of the youth ‘who daily further from the east must travel’, and yet in Christ we

turn, a good Advent word, back to the east, we are re-oriented to where through the saints we have our intimations of immortality. People, look east.

By facing east in Church we are all drawn to the image of the Cross on the altar and to the tabernacle. Cross and altar are many faceted symbol of Christ’s sacrifice, Christ’s presence, of Christ as the source of all nourishment, Christ who feeds us and the world with the gift of himself. Like all who read the Scriptures with care, we agree with the Epistle to the Hebrews that Christ’s sacrifice was offered once when he bore the sins of the world on the cross. And yet, in a real sense, his sacrifice is eternal, for he pleads that sacrifice eternally before the Father.

People, look east, for what happened 2,000 years ago in the orient was an eternal moment, drawing us back to that place where heaven and earth were reconciled. And we will only know the full and wondrous length and breadth and height and depth of that sacrifice when we see its fruit, when at last heaven and earth are made one, and a new humanity is revealed, and Christ is owned by all as Lord and King. The subdued purple hangings remind that God’s ultimate purposes in Christ are yet to be fulfilled, which makes our prayer,

Marana tha, ‘Our Lord, come’, ‘thy kingdom come’ all the more urgent.

Advent is a time to be re-oriented because Advent is the great season of hope. ‘The people who walked in darkness have seen a great light’. People, Look east!